The road out of Page is a two lane highway with infrequent passing lanes and no turn outs. Little towns are scattered along the way. Signs mark their existence, trailers huddled in the distance, and a Dollar General store at the edge of the road. It’s the Fourth of July weekend and there are more vehicles traveling, boats and ATVs trailing behind. After a while, the traffic dwindles and I’m alone on the road, music on the radio, surrounded by the shapes and colors of the desert, and the horizon where it meets the sky.

A sign informs me that Four Corners is thirty miles ahead. I look forward to seeing the monument there, and stopping to stretch my legs. I’m disappointed when the Navigation Lady’s voice tells me to turn left onto HWY 191, directing me to the nearest Tesla supercharger. There are long stretches with no radio reception, no music. In the silence, my mind hopscotches from this thought to that, from nothing in particular to wonderment at the majesty of nature, to realizations of mistakes I’d made in not planning this journey in advance. Spontaneity is a wonderful thing, but I could have planned the route better.

It’s been a long while since I’ve seen another vehicle, or even a wayward herd of cows. I feel uneasy with the remoteness of the road when Navigation Lady informs me not to exceed fifty-five miles an hour in order to make it to the supercharger. I look at the charge indicator. It’s in the orange zone. Half an hour later, she says that I should not exceed fifty miles an hour to make it to the supercharger. I’m not panicking, not really. Trust the navigation system, I tell myself. The road seems endless, time and distance elongated. Maybe I should pull over to the side and walk around the car, get a breath of air, but it’s one hundred degrees outside, so I take a few deep breaths and slow down to forty-five, for a little extra assurance. After a while I see a truck driving towards me, and then fingers of a town reach into the desert.

I arrive in Blanding, UT with thirty-five miles of charge left, impressed with the magic of engineering in the guidance system of this vehicle. I bless Elon Musk, plug Freedom into a supercharger and walk to the Visitor Center. It’s welcoming, with clean restrooms open 24/7, WiFi, and a playground. There’s a museum of Pioneer history inside. It’s nearly closing time when I arrive, so I don’t linger. I have a delicious wrap at the Patio diner across the street. In twenty-five minutes, I’m on my way to Cortez, CO to visit the Pueblos in and around Mesa Verde.

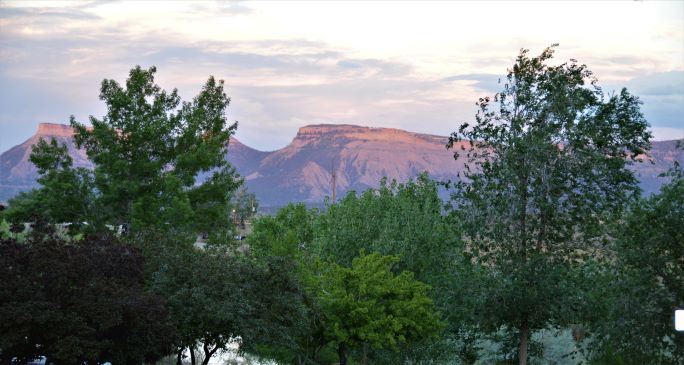

I stay at Eco Bella Organique, an Airbnb in a quiet neighborhood at the edge of Denny Park. Inside a private courtyard, the room is cozy, filled with light, and tastefully decorated. The host, Pauline, is friendly and gives helpful information about places I want to see. The five days I spend here are restorative. Pauline is a masseuse; naturally, I had to have a massage. It’s the best massage I’ve had in a long time. I feel the tightness from sitting in the car for long hours release.

The evening air is pleasant, and we chat on the patio, her dog, Honeybee, curled at our feet, her kitten, Tiger Lily exploring. We talk about love and I see a shooting star streak across sky.

If you are ever in Cortez, I highly recommend Eco Bella Organique.

The road to Chapin Mesa is closed for re-surfacing, and I am unable to visit Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde’s largest cliff dwelling. I spend the day at Far View sites, fascinated by what I see, imagining what it would be like to live in this way.

The Pueblo people moved onto Mesa Verde around 550 AD. They lived and flourished there for seven hundred years. Between 1150 to 1300, thousands of people lived there. The cliff dwellings were built with rectangular sandstone blocks, mortared with a mix of dirt and water. They gathered wild plants, and hunted deer, rabbit, squirrels, and other animals, and farmed the three sisters: beans, corn, and squash. They worked their fields with digging sticks, and built check dams across draws to hold rain and snow. Dogs and turkeys were the only domesticated animals. Turkeys provided feathers for ceremonial use, arrow stabilizers, and blankets. It’s believed that the turkeys’ feathers were gathered and humanely removed during the molting process twice a year. The bones were used for musical instruments.

By about 1300, Mesa Verde was deserted. Crop failure from drought, over-hunting, and clearing of trees for building and firewood, changed the habitat for animals that the Puebloans depended on for food. Archeologists believe that around thirty thousand people lived on the mesa at the time. They migrated south to the areas that are now New Mexico and Arizona.

Lower left: Corn was ground here using stone metates. Lower right: This reservoir is designated a Historic Landmark by International Civil Engineers. It is thought that it was also used as a ceremonial site.

Sand Canyon Pueblo is one of the largest prehistoric settlements in the region. I drive on gravel roads, passing an occasional farmstead, to the upper trailhead. There’s a small parking area and a few picnic tables. A family of four sits at a table, eating snacks and looking at a map. I wave and head out on the trail. At first, the trail is flat and sandy, and then descends along a ledge, not unlike the Bright Angel Trail in Grand Canyon, but narrower. I start feeling the effects of height vertigo. Other than the family I passed, there are no other hikers. I decide this is not a hike to do alone, and head back up.

I sit on a boulder in the shade of a pine tree. It’s silent, peaceful, only the chirps and cheeps of birds having a conversation I wish I understood, and a gentle breeze whispering in the canyon. I watch the sky hoping to see an eagle. I read a booklet on Archeological Evidence and Scientific Insights. I write for a while, and then allow my senses to be alive, feeling the heat that is held in the earth, smelling the sweet, pine scented air, unaware of time.

I can’t help seeing a correspondence between the Pueblo migration and the condition the world is in today. Drought, over use of natural resources and overpopulation caused the Puebloans to leave their home in order to survive. We are seeing this happen globally, complicated by wars, political struggles, and environmental changes, as well as over population, and over use and misuse of natural resources. Now the situation is more dire. It’s estimated that the worldwide population in 1300 AD was around four hundred million; today there are nearly eight billion people living on Earth. Harvard University sociobiologist, Edward O. Wilson, estimates that the maximum population Earth’s available resources can carry is nine to ten billion people. The world population is estimated to increase to nearly ten billion by the year 2050.