As I gathered my thoughts on the year that just closed, the word bittersweet came to mind. I might throw in upheaval, loss, and heartache. I know that I am not alone in this; 2023 was a difficult year for almost everyone I know, but, there was also magic, miracles, renewal, and growth.

In February, there was a sudden change in my life. I drove to Tucson, Arizona and Las Cruces, New Mexico to sort thigs out. I found solace at White Sands National Park as I wandered the desert dunes, enraptured by the otherworldliness of the powdery white sands against the blue sky. The silence there evoked a sense of peace, and I found the strength to do what I needed to do to move on.

A little over two years ago, the cosmos sent me an invitation to consider Montana as a place of residence. It had never crossed my mind as a place to live before that day. It’s too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter were among the long list of reasons why I wouldn’t want to live there.

The first bidding came as a thunderbolt in the form of a blue eyed Montanan at a Tesla Supercharger. We had a twenty minute conversation that held the essence of eternity.

The second summons came in my mailbox two months later, as a beautiful trifold brochure: Come home to Montana it said.

Instead, I took a detour to Colorado. Some lessons needed to be learned there, and now I had to move again. It was time to listen to the cosmos and try Montana. After a stressful month of looking for a rental on the internet, like magic, the cosmos guided me to the best place to live. Everything I want and need is here. It’s a small city with a strong cultural heartbeat, a river runs through it, and it’s surrounded by wild nature.

To affirm that I had come to the right place, I soon met friendly people who welcomed me into their social circles. There were trails to walk, sunsets to watch, and hillsides and mountains to climb and explore. I arrived just as spring began to unfurl the buds on trees into perfumed flowers. Soon the fields and hillsides were abloom with dandelions, arrow leaf balsamroot, lupine, shooting star, and many more wildflowers that continued to blossom throughout the summer and into the fall. I found favorite little spots in the woods, along the creek to hide and heal, to meditate, let go, forgive, and practice unconditional love.

In November, my ophthalmologist informed me that pressure on the optic nerve in my left eye was too high. He performed eyesight saving surgery by inserting a microscopic-sized stent in that eye. The surgery took fifteen minutes, but healing and recovery continue. After surgery I said that I was grateful to have my eyesight, and that I didn’t live a hundred years ago or I might have been blind. Dr. Berryman said that I would most surely have been blind in that eye; even sixty years ago we didn’t have the technology for this surgery.

I believe that when I have a problem with my body, there is something I need to learn about myself. I’ve been meditating on what have I lost sight of? What is it I do not see? What do I not want to look at? What have I turned a blind eye to?

And every day I look at the world anew, even more grateful for the gift of sight.

Mid-December, my brother Nick called and asked If I wanted to spend Christmas with my family. It had been five years since I visited; the time had come to see my siblings and extended family again.

It was a wonderful reunion filled with laughter, love, and delicious Italian food. I stayed with Nick and my sister-in-law, Cathe Ann, for a few days. They are both equine veterinarians, and I made the rounds on Christmas Eve morning with Cathe Ann. Most of her calls were to horses that were foundering. First we visited her horse, Leo.

The next few days were filled with Christmas festivities and the joy of reuniting with family. The day after Christmas, my sister Kathy and I made pitta, a traditional Calabrian holiday pastry. The dough is made with red wine, cinnamon and cloves, rolled with nuts, raisins, and honey. The next day was Girls’ Day. My sisters Kathy and Sandy, their daughters, Dona, Tara, Jackie, and Dina, and granddaughters, Cassandra and Giana, all gathered at Kathy’s house. We talked and laughed all afternoon, telling stories of growing up, and loving memories of our parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

Since my flights arrived and departed at JFK in the middle of the night, I stayed with my cousin Teresa at her home in Flatbush. It was the highlight of the visit. This house has been in the family for seventy-six years. My mother’s parents, Grandma Katie and Grandpa Armando, Uncle Pat, Aunt Mary, and Uncle Ralph bought the house, but it’s always been referred to as Grandma’s house. Teresa was a baby when they moved in, and she grew up there. She moved back to the house about fifteen years ago to care for her parents as they aged. Aunt Mary passed away two years ago, and now the two family, three story house is more than Teresa needs. It’s been sold and she’s moving to Long Island.

Grandma Katie was an excellent cook. Her Sunday gravy was luscious. Her homemade tagliatelle was light as a feather. Sometimes there was lasagna, but that was usually for holidays or a special occasion, as was ravioli, manicotti, or cannelloni. Meals were to be delighted in and consumed slowly, with conversation. There were numerous courses, from antipasto to dessert. After the main courses were served, my father and uncles took all of us kids for a walk to Marine Park to play on the swings and jungle gym. When we returned, the dishes were done, coffee was perking, and there was clean linen on the table along with an array of Italian pastries, or cakes from Butter Bun that Uncle Pat bought in the City, or some of the traditional pastries that Grandma made: pitta, cuzzupa, strufoli, tirali…she was as good a baker as she was a cook.

There was a time during my early adolescence that Aunt Mary would give us girls Toni permanents after dinner. I remember the stench of ammonia in the air as each tress was tortured into submission, followed by the thinning shears. “You have too much hair,” Aunt Mary would say. One day I conjured up the nerve to say I didn’t want a perm. She said, “Okay,” and I never had another Toni. If I had known it would have been that easy, I would have spoken up sooner.

We’d have a snack before the drive back to Long Island, and were sent on our way with grocery bags filled with leftovers of Grandma’s delicious food.

Grandpa died when he was fifty years old, and Grandma was still in her forties. In Italian tradition, she mourned by wearing black for a year, but she continued to work during that time, as a seamstress in the New York City garment district. She worked until she was seventy-two. She didn’t talk a lot, but when she did, it was memorable. Some of her famous sayings are: “blood is thicker than mud,” and “money is the evil of all roots.”

I went to Brooklyn College, and rather than commute from and to Long Island every day, I lived at Grandma’s house. It was a short bus ride from Nostrand Avenue and Kings Highway to the college. I lived in the basement and remember great conversations with Uncle Pat and Uncle Ralph. I had a parttime job at Rainbow Shoppe, a ladies clothing store, and worked some shifts with Aunt Mary. Sometimes she’d take me to lunch at Dubrow’s and wanted to know all about what I was learning at college. She said she wished that she’d had the opportunity to go. Teresa and I danced to rock music when we helped clean up after dinner, or she’d come downstairs and we’d talk and listen to music together.

Eventually, I became an Airline Hostess and followed my dreams to the west coast, but I returned to visit the family as often as possible. Of course, I visited Grandma’s house whenever I was in New York, and my children got to grow up with their cousins and be loved by grandparents, aunts, and uncles, just as I did.

When Grandma Katie was eighty seven years old, she fell and broke her femur. The doctor told her that she would never walk again. She looked him in the eye and said, “That’s what you think.” Of course, she walked again. She used a cane when she was outside the house, and a walker in the house that was hidden away when anyone visited. Grandma lived to be one hundred five years old.

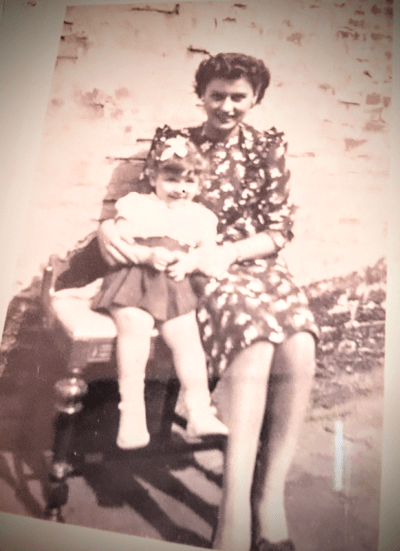

Grandma Katie is role model for me. She accepted whatever life threw at her without complaint and a good attitude. She lived a quiet, humble life, and was there for her family in the things she could do. I never saw her angry or say a bad word about anyone. Her generation wasn’t given to saying “I love you,” but you could see it in her eyes when she looked at you.

There are many precious memories of life lived in this house, of dear family members and the times we shared, memories that I tuck in my heart and carry with me. I left the house at 3:30 A.M. on December 29th. Saying goodbye as the Uber driver slowly drove past it, I knew that this isn’t merely the close of a chapter for my family, it’s the end of an era.

“I was born into a culture that lived in communal houses. My grandfather’s house was eighty feet long. It was called a smoke house and it stood down by the beach along the inlet. All my grandfather’s sons and their families lived in this dwelling. Their sleeping apartments were separated by blankets made of bull rush weeds, but one open fire in the middle served the cooking needs of all. In houses like these, throughout the tribe, people learned to live with one another; learned to respect the rights of one another. And children shared the thoughts of the adult world and found themselves surrounded by aunts and uncles and cousins who loved them and did not threaten them. My father was born in such a house and learned from infancy how to love people and be at home with them.” Chief Dan Geroge, Tsleil-Waututh First Nation

Happy New Year. May you find fulfillment of all you wish to achieve. May you find peace within, peace in your relationships, peace in your community. May there peace on Earth.