O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

Katherine Lee Bates

Late in July there was an unexpected, severe storm in Missoula. One minute it was daylight, the next, the sky was black. There was one lightning strike after another, the earth rumbled with thunder, and fierce winds gusted up to 110 MPH. Tree limbs and all sorts of debris flew through the air. Entire trees and power lines were knocked over. I was without electricity for thirty-six hours, but consider myself fortunate, some areas were without it for nearly two weeks.

The wind blew the air handlers for the air conditioners off their bases on the roof of the apartment building where I live. The one for the wing I live in was severely damaged. After twelve days of sleeping in a stuffy apartment, I decided I needed to go somewhere.

I’m in the midst of writing a novel that takes place in the “Golden Triangle,” where the main crop is wheat. Even though the story has nothing to do with wheat or farming, it seemed a good idea to explore the area to get a sense of place for my writing. The drive began on HWY 200 through twisty, forested roads before flattening out to farmland. There was much more to see, but first, a stop in Great Falls.

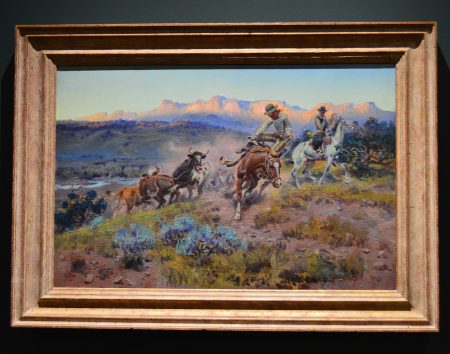

Charles Marion Russell ~ The Cowboy Artist ~ Painter of the West

“If both hands were cut off, I could learn to paint with my toes. It is not in my hands but heart what I want to paint.” Charles Marion Russell

The C. M. Russell Museum is located in a neighborhood of charming Victorian houses where Charles Russell lived with his wife, Nancy. Born in 1864 in St. Louis, MO, Russell grew up on tales of the West and wanted to be a cowboy. He struggled at school, but art was always part of his life. When he was sixteen, his family arranged for him and a family friend to work on a sheep ranch in Montana. He didn’t last long at the job, but he did meet a trapper named Jake Hoover and lived with him for two years, learning about the land and studying the animal form.

And then he became a cowboy, a night wrangler, for twelve years. He carried watercolors and brushes in his bedroll, and using whatever carboard and paper he could find in camp, he sketched the animals, the landscape, and the other cowboys. The winter of 1886-87 was severe. The owner of the O-H Ranch where Russell worked, sent the ranch foreman a letter asking how the herd had fared through the harsh weather. Instead of a letter, the ranch foreman sent a postcard sized watercolor that Russell had painted. It showed a gaunt steer being watched by wolves under a gray sky. Russell had captioned the sketch, “Waiting for a Chinook.” (Warm, dry winds.) The owner of the ranch displayed the postcard in a shop in Helena and Russell began to get commissions for illustrations. Later, Russell painted a more detailed version of the sketch that became one of his best known works.

In 1888, Russell lived in Canada for a year with the Blood Indians, a branch of the Blackfeet Nation. His paintings of his time there showed great detail, even of the beading on moccasins. He had a great affinity for Native Americans and became an advocate for them. He supported the Chippewas in their effort to establish a reservation, and in 1916 congress passed legislation to create the Rocky Boy Reservation in north central Montana.

Russell became a full time artist in 1893. He married Nancy Cooper in 1896. Nancy marketed and sold his art, and Russell became an acclaimed artist. His art captured the old west before it was lost to the call of Manifest Destiny, the lust for natural resources, and the industrial age. He is also known for his use of color. In his lifetime, Russell created more than 4,000 works of art: paintings, sketches, and sculptures.

In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. It is the second largest wildlife refuge in the lower forty-eight states with approximately 1.1 million acres of native prairie, forested coulees, river bottoms, and badlands, much of which are portrayed in Russell’s paintings.

I find Russell to be a fascinating human being as well as a gifted artist. PBS created a documentary “C. M. Russell and the American West.” Watch it if you’d like to learn more about him and see more of his paintings. If you are ever in Great Falls, the C. M Russell Museum is worth a visit.

The Golden Triangle

The longest leg of the Golden Triangle is from Great Falls to Havre. Driving north on US87 the vast northern prairie is strewn with sixteen hundred farms threaded together with small towns or truck stops with gas stations and cafes. Wheat fields stretch out to a horizon marked with buttes or shadowed by massive cloud formations. Barns and steel silos are clustered together, reaping equipment and trucks are parked nearby. I pass old wood silos that look as if they are ready to crumble, but stand as proud reminders of their past service.

The Mighty Mo

There are pull offs at historic sites that provide not only information, but also beautiful vistas. My first stop is at a loop in the Missouri River. The Missouri joins the Mississippi River in St. Louis, Missouri. Starting there, in May, 1804, Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery followed the 2,540 mile long Missouri River to its headwaters in Montana, at the confluence of the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin Rivers. They arrived in July 1805.

They followed the Jefferson River to Missoula, and then to Travelers’ Rest in Lolo. From there it was an arduous overland trek through the mountains until they reached the Clearwater River in Idaho, into the Snake River, and then the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean, where they wintered in present day Astoria, Oregon.

They returned to St. Louis In September, 1806. During the expedition, they encountered over seventy Native American tribes and learned and recorded the languages and customs of those tribes. They mapped the topography of the land, rivers, and mountain ranges and described more than two hundred new plant and animal species, with information about their natural habitat. They brought back many artifacts as well as plant, seed, and mineral specimens.

Farther up the road is the oldest town in Montana, Fort Benton. Established in 1846, it was once the world’s largest inland port. The fort was built for the fur trade. Steamboats and travelers arrived in 1860, and then the gold seekers in 1862. It became a main destination and supply hub on the upper Missouri, and was called “the Chicago of the West.” By the 1890s, railroads had become the favored form of transportation, and the era of steamboats ended. Fort Benton is a National Historic Landmark.

The landscape rolls along and I stop when I can to appreciate the beauty of the land. Besides the farmland, there are many opportunities for outdoor recreation: camping, fishing, and hiking. There is so much more of this beautiful area that I would like to spend time exploring.

When I arrived in Havre, I’d been on the road for two and half hours and needed to stretch my legs. I plugged Freedom into an EV charger and walked to the H. Earl Clack Museum. There are exhibits of local history, as well as dinosaur bones. The museum is part of the Dinosaur Trail, made up of fourteen sites throughout Montana.

The Golden Triangle is a vital part of Montana’s economy, and the wheat industry is the largest contributor, producing 186,705,000 bushels annually. Eighty percent of Montana’s wheat is exported. About 2.2 million acres of hard red winter wheat and spring wheat are planted annually. The next time you eat bread or pasta, consider that it may have been made of Montana hard winter wheat, or Montana spring wheat for your pancakes, cakes, and pastries. Other crops such as oats and barley, as well as peas, lentils, chickpeas, and canola are also part of Montana’s farming industry.

On the drive back to Great Falls, the side of the road was lined with wild sunflowers. They looked so joyful, I had to stop and walk among them. After driving around southwestern deserts and the mountains and prairies of the west the past four summers, I have come to associate them with this part of the United States and the month of August.

If I were in charge of the Department of National Anthems, I would choose “America the Beautiful” for the United States. Besides being difficult to sing, “The Star Spangled Banner” was written after a battle during the War of 1812. I think we should change our focus from war to America’s beauty and abundance, and all the good that can come from brotherhood.

O beautiful for spacious skies,

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America! America!

God shed His grace on thee

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea!

Katherine Lee Bates